Impact A Social Worker’s Struggle to Keep Her Professional and Personal Worlds From Colliding

Don’t hit that bike, don’t hit that bike, I repeated to myself. Learning to drive at 16, I tried vigilantly to avoid obstacles in the road. But my caution had no bounds; I would over-focus on that bike, and the car would veer directly toward where I least wanted it to go.

Living and Learning

Fifteen years later, the road ahead looked straight and clear. I was happily married, eager to have children, and immersed in my work as a clinical social worker at a non-public school for special education. The students there were so impaired, so unpredictable that they could not be contained in any kind of special program available in the public schools. This school served children ranging in age from 4 to 21, from learning disabled to emotionally disturbed to profoundly autistic, from socially avoidant to conduct disordered to bi-polar. Each day held new crises, altercations, interventions and explosions of conflicting tempers, pathologies and pharmacologies.

These children fascinated me. I was challenged by their challenges and open to their possibility. Nothing intrigued me more than finding a bridge to a remote child. My greatest triumphs came in devising new ways to reach and teach these compelling children.

Steeped in this brew of disability, I passed my days providing therapy, defusing daily crises and debriefing combatants. And when all was quiet, I studied case files: brick-thick stacks of evaluations by psychologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, educators, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, and many, many more.

I read them all with professional interest, took relevant notes, and filed them away. And then I became pregnant. Right away my friends expressed worries for me: “Aren’t you scared, working at a place like that when you’re pregnant? What if one of those crazy kids tries to hurt you?” But physical safety was low on my list of worries. I had never been hurt on the job, and felt pretty confident with my training.

My Turn?

Something else entirely had begun to frighten me about working where I did while pregnant. Each day I came face-to-face with the myriad things that can go awry in the miraculous process that creates a human being. Why wouldn’t it happen to my child? I continued reading evaluations, but from a new, deeply personal perspective. Now I focused on the factors that professionals and especially parents posit as explanations for “what went wrong.” Every evaluation suggested another cause for the child’s dysfunction, dating back even before birth: “Pregnancy was notable for mother’s use of cocaine in the second month.” “Delivery was notable for use of vacuum extraction.” “Labor was notable for use of Pitocin/Demerol/epidural.” “Pregnancy was notable for premature delivery at 34 weeks … for mother slipping on the ice in seventh month … for mother’s exposure to Chicken Pox / Fifth’s Disease / Salmonella / household cleansers/ asbestos / carbon monoxide / pesticides,” on and on.

Each evaluation offered me a new worry, so I resolved to shield myself, and my child, against any prenatally “notable” force. I would ensure that disability would not happen to my child. I believed my first maternal obligation would be to protect my child from all potential agents of harm. And I believed it was within my power to do so.

I focused on avoidance, on circumventing every imaginable hazard: Don’t hit that bike, don’t hit that bike. I was vigilant. I ate carefully and organically, kept a distance from colds and illnesses, and exercised regularly and mindfully. I ingested no pain-reliever or antibiotic; allowed myself no alcohol, no caffeine, no soft cheese, no cold cuts, no tuna. I accepted no Novocaine when I had two teeth filled. And I powered through my 28-hour labor with no drugs. Through it all, I felt virtuous and vital and clear of purpose. Finally, after nine months of fastidious safekeeping, our beautiful son arrived. The instant of his birth was dazzling. The climactic pronouncement: “It’s a boy!” The thrill of finally meeting him, seeing him, having him. A breathtaking realization: “I’m a mother!” All packed into a fraction of a single electric instant.

And in the midst of it all, right within that very instant of astonishing exhilaration, I saw it on the doctor’s face: Something was wrong. Here was the unthinkable possibility that everything was less than perfect when nothing short of perfect will do. The doctor told us that our son had a small vascular problem that could require several surgeries to correct. He said it was “likely due to some flaw in fetal development, possibly in the second trimester.” He said, “Perhaps you had a virus.” Excuse me? No, I did not have a virus.

My husband remembers me asking him, that very first night: “If that went wrong, what else might be wrong?” The answer to that question unfolded over the next several years. As our son grew, I diligently checked off developmental milestones as they were achieved: Eye contact? Check. Sleeping through the night? Check. Rolling over? Check. Wait a minute – what happened to eye contact?

Our Challenge

By the time our son was 3 we had some real concerns. He didn’t know how to play with other kids. He grew anxious or frustrated whenever anything was new or challenging to him.

He wouldn’t separate. He couldn’t count objects, couldn’t make eye contact, and often dissolved into unpredictable, high-intensity meltdowns. We were overwhelmed and exhausted. And what exactly was going on remained frustratingly elusive.

Over the years, our road together has been a bumpy one. Our son rebounded easily from three vascular surgeries that seem to have scarred us in some ways more than they did him. He has benefited from a wide variety of therapies for a wider variety of issues. At school, he has been placed in a special education program where he works diligently.

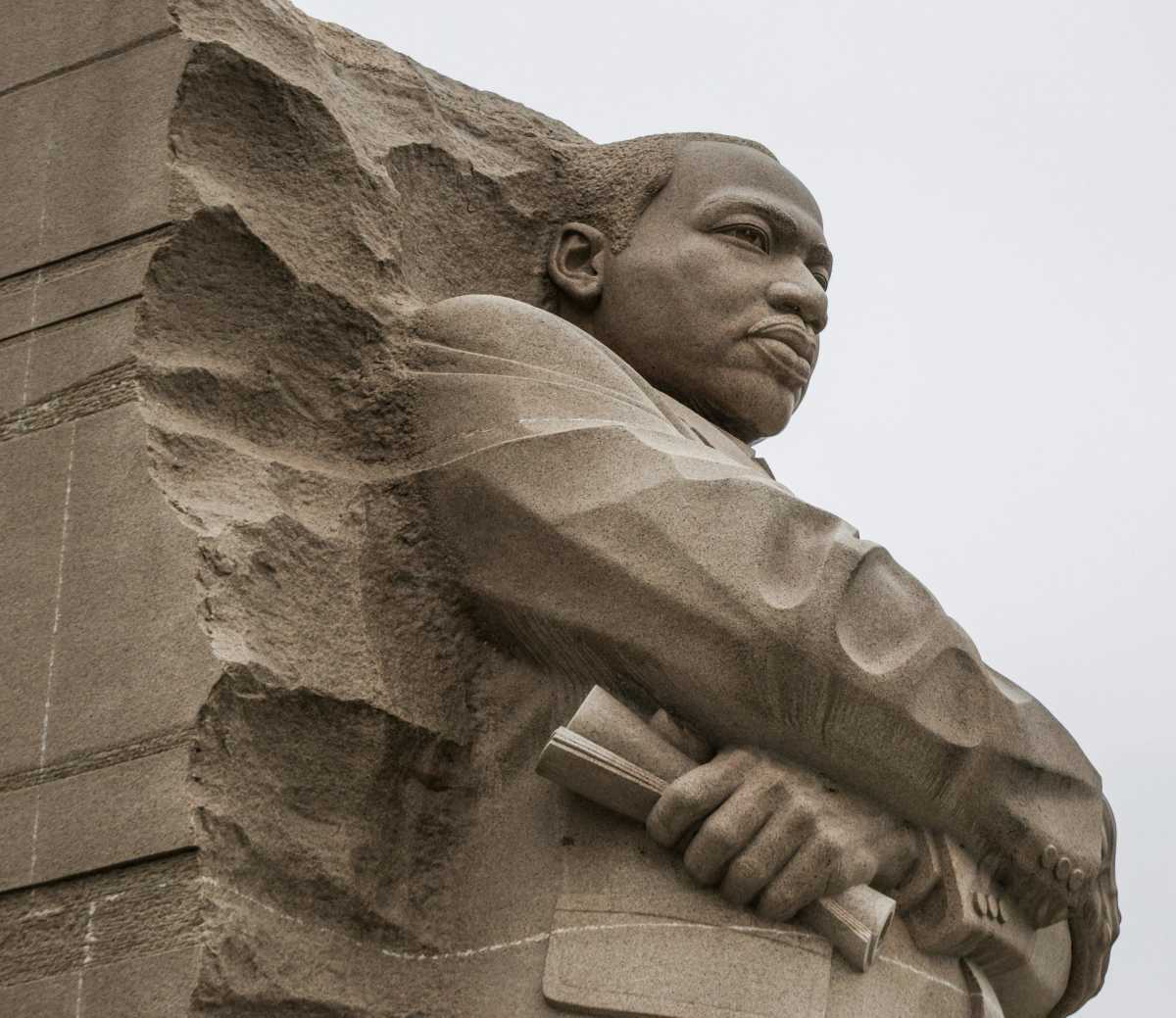

We shore him up with reliable routines, healthy food, social prompts and upbeat reassurances. Today our son is a bright, feisty 12-year-old. He is articulate and funny, affectionate and handsome. He loves to play, imagine, ask questions. He has an innate ability to memorize dates and historical events that confounds adults and astounds peers. He can be impulsive, provocative, hyperactive, rigid and obsessive. Transitions must be scripted for him, until they become as predictable as the movies he watches and quotes over and over again. He can be unstoppable as a steamroller, barreling through conversations, laying flat the feelings of others – especially his little sister. He cannot sustain focus and eye contact is still fleeting. He bears heavily the Special Ed Badge of Membership: a brick-thick stack of evaluations, as weighty as our worries.

Sometimes, in my lower moments or his lower moments, I look at my son and wonder how we got here. One day I feel disbelief: How could this have happened, when I worked so hard to prevent it? Another day I feel bitter: My friend drank soda with aspartame every day during her pregnancies and her kids are just fine. Another day I feel blameless: I know I did everything I could to prevent this, so it must have been “meant to be.” Many days, like most mothers of children with special needs, I find ways to blame myself for my son’s difficulties. In my case I consider whether I was too anxious, too uptight, too worried during my pregnancy – if I had relaxed more, hadn’t been so vigilant, maybe he would have been OK.

But in truth my son has taught me lessons of humility and humanity that I would never have learned without him.

During my pregnancy, I fixed my gaze on that bicyclist by the side of the road: Don’t hit that bike, don’t hit that bike. Somehow or other, despite or because of my best efforts, I veered straight toward it. I hit that bicyclist head-on, and we are both bruised and battered and tangled inextricably together. So we sit, he and I, by the side of the road, and watch other cars and bicycles glide easily, carelessly past us. And we hold each other and love each other and feel so deeply thankful that our worlds collided.

Barbara Boroson, LMSW, lives locally and is the author of Autism Spectrum Disorders in the Mainstream Classroom: How to Reach and Teach Students with ASDs (Scholastic Inc., June 2011), a guide for teachers seeking to integrate students on the autism spectrum into mainstream classrooms.