Young children aren’t usually known for intense concentration. To the contrary, kids are expected to bounce from one activity to another even though they don’t have much of an attention span. That’s why parents are surprised by what they see when they tour Eton Montessori School in Bellevue, Wash. Children as young as 3 happily engaged in independent, focused work for long stretches.

Parents are just as surprised by what they don’t see – no lecturing teachers prodding reluctant kids to complete assigned work. “Our children are self-motivated. Our teachers don’t stand over them, telling them to be quiet and get back to work,” says Feltin, who founded Eton School in 1978.

This ability to focus at a young age is a hallmark of Montessori education, but it’s revolutionary to parents who haven’t seen a Montessori classroom in action.

Montessori learning is hardly novel – Maria Montessori’s first school opened its doors in 1907. But a trend toward mindfulness in education is sparking new interest in this century-old style of education, and new science is showing how this type of learning benefits today’s young minds.

Mastering Mindfulness

In the past decade, organizations like Mindfulness in Education Network, Association for Mindfulness in Education, and Mindful Schools have sprung up, training teachers, hosting conferences and producing research aimed at helping children become more focused, motivated and intentional in the classroom.

Just what is mindfulness, exactly, and why does it matter? Mindf

Dr. Steven J. Hughes, a pediatric neuropsychologist specializing in attention, concentration, planning and organizing –

a set of traits known as executive functions – defines mindfulness as “sustained positive engagement.” Other scientists refer to a “flow” state of prolonged, energized work that produces both calm satisfaction and profound joy in learning.

Whole Body, Whole Mind

Maria Montessori didn’t coin the term “mindfulness,” but she was an early advocate for sustained focus and internal motivation. Her methods deliberately encourage intense concentration as the best context for early learning.

Montessori’s approach to motor development actually stimulates cognitive development and deep concentration, says Hughes. When children begin Montessori education at age 3 or 4, they work on motor-skills activities like sweeping, polishing silverware and pouring. These aptly-named “practical life” activities prepare kids for greater independence and self-reliance in daily tasks, but there’s something bigger going on – the development of higher cognitive functions essential to concentration and attention.

Montessori tasks like wiping a table or washing dishes develop fine-motor control, but they also activate areas of the pre-frontal cortex essential to executive function, which paves the way for greater concentration and focus, he says.

“Dr. Montessori wrote about the close relationship between cognitive development and motor development in 1949. Fifty years later, scientists made the same connection.” This whole-body approach is part of the reason numerous studies show that Montessori-educated children have an academic edge over children educated in traditional classrooms, he says.

Happy Work: Environment, Schedule, and Shared Focus

One way Montessori promotes focus is through a carefully-prepared environment, a key component of Montessori learning. In Montessori classrooms, specially-designed materials – from child-size brooms to lacing cards to counting beads – are prepared to be aesthetically appealing and accessible for young children; simplicity, beauty and order are paramount.

“Montessori environments are designed to be attractive and appealing, and to allow children to make a choice. Children get to look around and choose what they want to do,” says Feltin. This important act of choosing one’s own activity promotes sustained engagement, says Dee Hirsch, president of the Pacific Northwest Montessori Association and director of Discovery Montessori School in Seattle. Montessori-taught children choose their own work from a palette of developmentally appropriate options that grow progressively more complex and challenging.

Montessori schools incorporate concrete learning goals into a child’s educational plan, but children are free to choose when and how to complete their work within a specified time frame. “That act of choosing i

s what allows a child to make a wholehearted commitment to their work. It’s what makes Montessori education child-centered,” says Hirsch.

When children are motivated by their own interests, deep concentration is a natural result, she says: “Kids are choosing what they want to focus on.” During a 90-minute work period, children can take their work through its beginning, middle and end. Working through this natural sequence promotes competence and mastery; children can repeat the activity as many times as they want, without being told to hurry up and move on to something else.

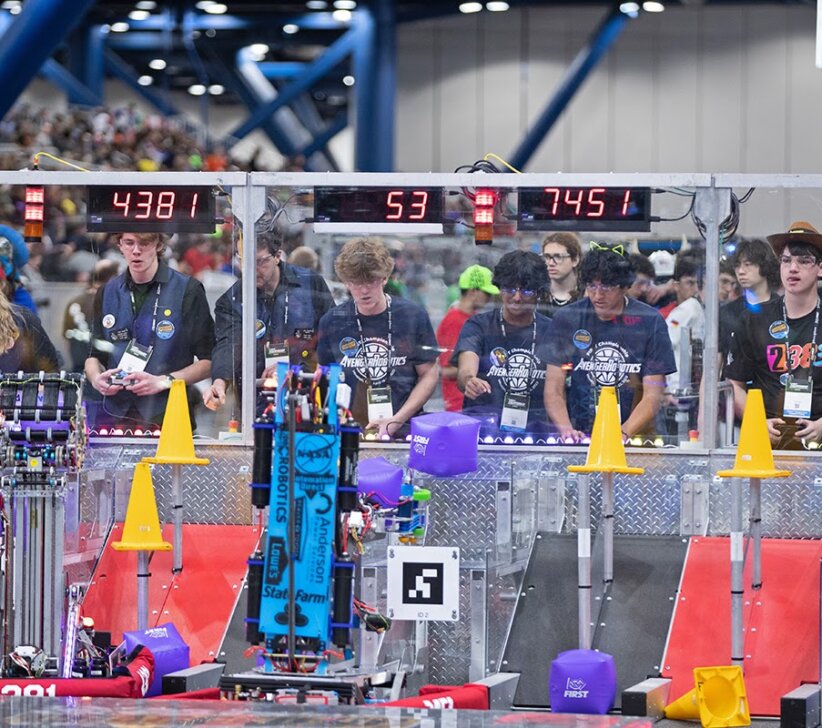

Though the terms focus and concentration conjure up images of a child working alone, mindfulness is not always a solo pursuit. Montessori-style learning helps kids learn the fine art of shared concentration by encouraging them to engage in tasks with a classmate or two – a critical skill in the age of teamwork.

Mindful Together

How does this Montessori-style mindfulness benefit children? Greater confidence, longer attention spans and natural self-motivation are a few of the rich rewards, according to Feltin. “What’s so wonderful is the confidence they gain. Their attention spans have been lengthened. They’re going to meet their academic goals, but they’ll do it more naturally because their motivation comes from within.”

But mindfulness isn’t something teachers can achieve for students – like every other outcome in Montessori learning, students have to work toward it themselves. “They’re not going to reach that state of mindfulness unless they get there themselves,” says Hirsch. “We can’t take them there, but we can go there with them.”

Malia Jacobson is a nationally published freelance writer specializing in parenting. She’s working on adopting Montessori-inspired principles of mindfulness at home.